By Andreas Schleicher

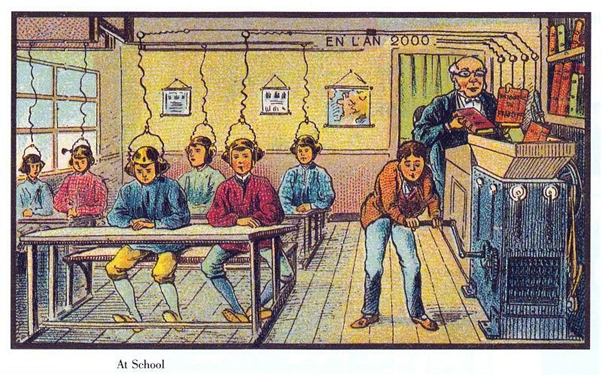

It’s hard to predict the future of education. In 1910, to commemorate the World’s Fair, the French artist Jean-Marc Côté produced a series of colourful prints depicting the year 2000. In one of them, a teacher is feeding textbooks into a machine, where the knowledge is transmuted into information delivered directly into the heads of students. A few years later, Thomas Edison predicted that books would soon be obsolete in schools, replaced by row upon row of students sitting passively in their chairs, receiving instruction from motion pictures.

Obviously, these visions of the future were widely off the mark in terms of actual academic and technological progress (not to mention demonstrating a misconception that education is merely a process of stuffing information into the heads of students). More recent projections about the future of education have fared little better: In 2015, at the UN summit on sustainable development, world leaders vowed to provide “free, equitable, and quality” primary education for all children, by 2030. In fact, between 2015 and 2023, primary education completion rates only increased by three percent, from 84 to 87%.

We like to tell ourselves that the story of human progress is one of continuous improvement, where technological innovation and socioeconomic advances march hand-in-hand. But the truth, of course, is that human development is messy. With just over five years to go before the end of the sustainable development goal (SDG) period, it’s worth reflecting on how technology is helping us to advance access to education, where gaps remain, and what more can be done.

When Sola Mahfouz was 11, her family pulled her out of school in Afghanistan after a group of men threatened her safety if she continued studying. Eager to learn, nonetheless, she began to secretly teach herself using digital learning platforms like Khan Academy. Sola later passed a college entry test, travelled to the US to study and is now a quantum computing researcher at Tufts University.

Sola is one of millions of students around the world who are seeking to build their skills through online learning programmes and MOOCs. Last year, Sub-Saharan Africa was the region with the highest growth rate in the number of people enrolling in online professional certificate courses, according to online learning provider Coursera. Between 2019 and 2023, nearly five million Africans were enrolled in courses on that platform alone.

MOOCs are a transformative tool and, as Sola’s story shows, they can be used to democratise access to education and overcome gender and other barriers. Thanks to falling costs for smartphones and wireless connectivity, more and more people are getting online. Among OECD countries, at least three-quarters of households have access to at least one smartphone at home. In Africa, internet penetration grew from under 10% in 2010 to 33% in 2021.

How scalable and impactful digital learning platforms are depends on a number of factors. Access to affordable, high-quality internet for all should be prioritised by countries so that anyone from any income group can access those resources. Pathways from online learning to formal qualifications should be put in place so that academic advancement is more clearly linked to better employment and socioeconomic outcomes. Government regulation and oversight should be established so that online courses are better linked to labour market needs, quality is assured and the data of students protected.

The rise of MOOCs is part of a larger trend towards a broadening of educational providers – private schools, non-profits, charter schools, micro-credential programmes and digital learning platforms. In the future, the education space will likely become even more crowded and more diverse, with a myriad of private, public and non-profit actors offering educational opportunities, many powered by AI, that are more flexible and tailored to the needs of individual learners than ever before.

Done well, new learning providers can help the furthest left behind. The citizen-led MolenGeek initiative is a good example. It aims to make the technology sector accessible to anyone in the historically deprived Molenbeek area of Belgium, regardless of their identity. Recognising that entry exams might exclude the most disadvantaged students, many of whom will have faced challenges with formal qualifications or testing, MolenGeek instead requires all entrants to develop their own project within the first six months of joining. This fosters the agency of students, empowering them to create their own roadmap to success while encouraging their creativity and problem-solving skills.

Success stories like this can be found in many countries but in the aggregate reach a small number of students compared to public education systems. In fact, despite a rapid diversification of the education playing field, few countries have yet found a way to create an educational ecosystem that crowds in a variety of types of educational providers, qualifications and platforms in an effective manner.

It’s important to mention that education isn’t a zero-sum game, and the entry of newcomers into the education system shouldn’t come at a cost to public education. A world where many different types of education providers coexist does not imply a diminished role for government. On the contrary, the role of government becomes even more important in ensuring that the system is equitable, fair, efficient and that it delivers the highest quality education to the highest number of students.

In addition to these characteristics, such an education ecosystem should be underpinned by a data ecosystem where information on students, educators and providers is comprehensive, interoperable and useable by all stakeholders to measure student progress, improve the quality of education, inform decision-making and facilitate an educational journey that accounts for credits earned in a variety of settings. Some countries have started to make progress towards such systems, but most have a long way to go. A great deal of work is still to be done to tackle issues around regulation, privacy and interoperability, tasks that are further complicated given the explosive progress of AI.

Finally, rising international student mobility, the internationalisation education provision and a changing technology landscape call for increased international cooperation. Organisations like the OECD and UNESCO, which provide internationally comparative data, foster peer learning and analysis on a wide range of education-related topics, play an important role in helping countries expand education access in an increasingly digital world.

Although it’s impossible to know what the world of education will look like a hundred years from now, we can be certain that the digital transformation is fundamentally altering how, why and where students learn. How governments anticipate, adapt to and guide those changes will be the key to ensuring that we put technology at the service of free, equitable and quality education for all.